Learn about a disease creeping into Ohio to destroy our oak trees.

Ask any ten people in Ohio what their favorite tree is and at least five of them will reply with an oak variety. And with good reason! Oak trees are among the most majestic of our trees, towering high alongside the other species of an Ohio climax forest (hickory, beech, maple). With limbs that themselves are as big as other trees, oaks inspire wonder even in the most jaded arborists who deal with large trees on a daily basis.

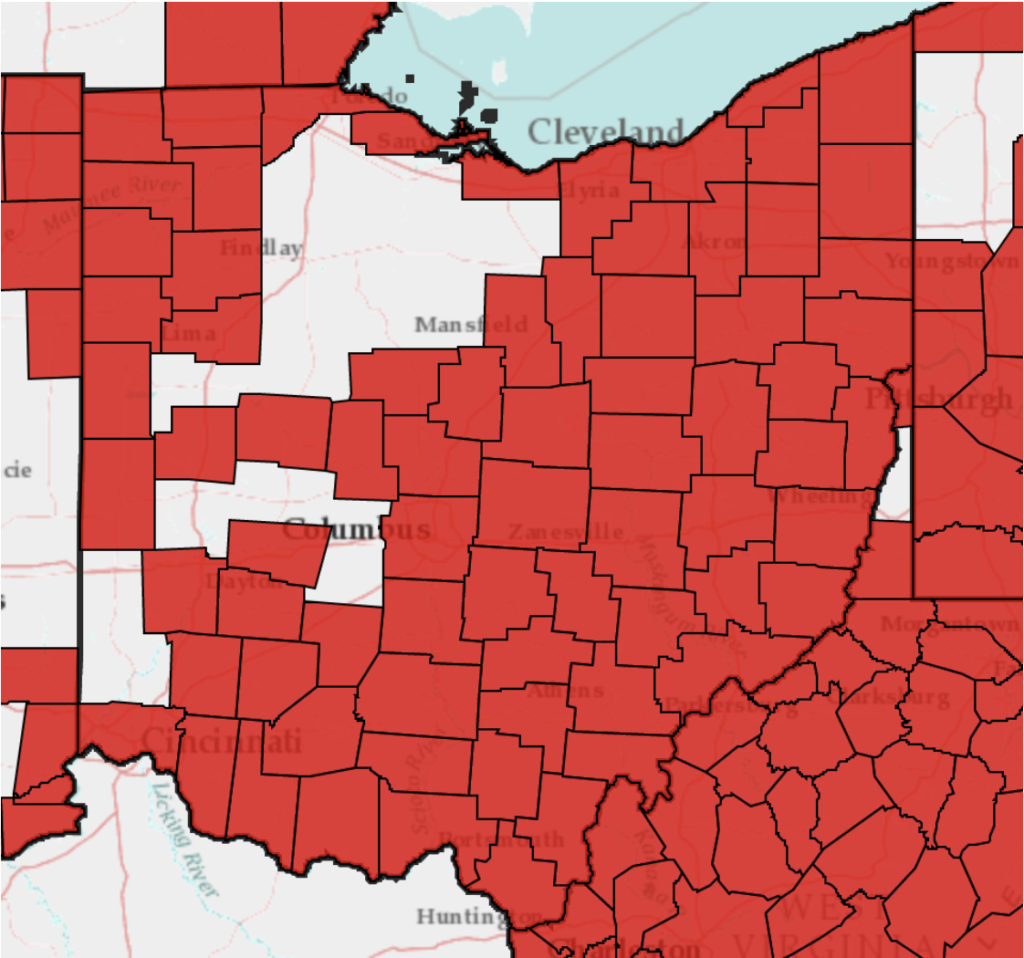

Oak wilt was first identified in the early 1940’s in Wisconsin, with subsequent discoveries in Texas (early 1960’s), and New York (mid 2000’s). It is believed that it is a non-native disease but its origin is unknown. It is also believed that it had likely spread through much of its current area of infection before its discovery. Currently oak wilt is present within 24 states, ranging from Wisconsin south to Texas, east to New York, but not very far south of Tennessee. There are still large swaths of oak habitat that are unaffected but many new disease centers are reported each year.

Source: Oak Wilt in the Northeastern and Midwestern States: A Story Map by the USDA Forest Service Northeast Region

Oak wilt is unfortunately a very generic name for a very specific disease. After all, oak trees can wilt for any number of reasons. THE oak wilt we speak of is caused by a fungal organism known as Bretziella fagacearum. In a nutshell, most of the oak species in our region are known potential disease hosts and will run the risk of infection if necessary conditions are met.

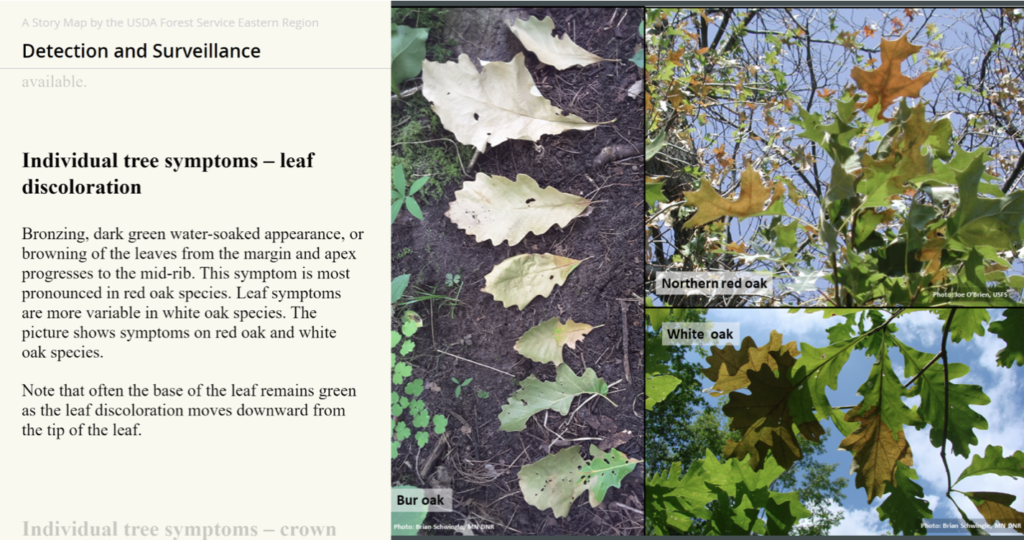

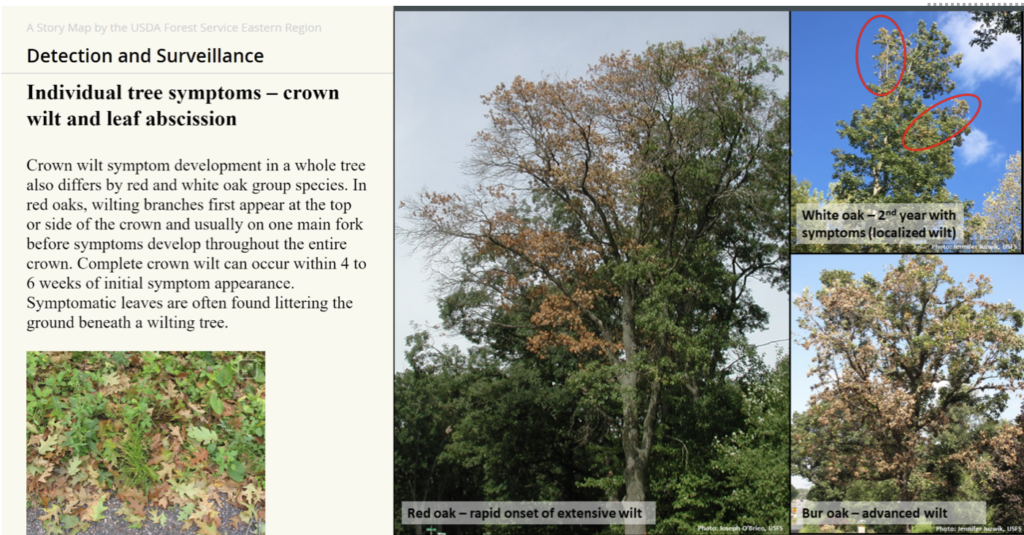

Once infected, the fungus moves through the vascular tissue of the sapwood (water conducting tissue) clogging up the “pipes”, reducing water flow. The fungus also induces a tree’s own defense systems to shut down vascular vessel elements that have been invaded. The result is either a quick, catastrophic wilting of the entire tree (in the case of species in the red/black oak group), or a slower decline over several years that will likely end in death (in the case of species in the white oak group).

How does all this happen? Why aren’t all oak trees already infected?

Well, there are several other actors in this play, and certain circumstances that favor infection. We will focus on a couple of the major characters and the part they play.

Sap-feeding beetles are attracted to their food, and as one entomologist has said, “they will fly as far as they need to in order to find food.” In the case of sap beetles, this could be anywhere from half a mile to several miles. How far they can fly and how high they can fly also depends on prevailing winds, local topography, and other factors. The important thing to note is that when there is a fresh wound on an oak tree, sap beetles are able to (possibly) scent them from afar and fly toward the wounded tree. If these beetles have been feeding on a tree that was infected with oak wilt, they will bring the disease inoculum with them.

In one of those amazing twists of nature, B. fagacearum can form sporulation mats just under the bark of certain infected trees. These mats are able to press against the bark from the inside and split the bark open, emitting a sweet, fruity odor that (attentive readers have already guessed) attracts oak sap beetles.

Other characters in the story are those which (or whom) cause wounds on oak trees. Oak trees are subject to storm damage, construction damage, line clearance pruning, tree harvesting or removal, and maintenance pruning such as that performed by arborists. All of these events will cause wounds (“infection courts”) that beckon to sap beetles for about three days, after which their attractiveness lessens. As mentioned above, the tree will likely be infected with disease if a sap beetle carrying fungal spores arrives at the infection court. The process described is called “overland spread” because the disease is able to hitch a ride through the air from one area to another via the insect vector.

Once a tree is infected at a new site, the primary method of transmission is called “underground spread”, and depends on the fact that oak trees (especially, but not necessarily, of the same variety) can form root grafts that are biologically active. That is, the contents of one tree are able to flow into another tree, and vice-versa. This includes pathogenic fungi such as our main character. At this point, communities of trees become vulnerable and begin to succumb to infection forming a recognizable, outward-expanding pattern of dead trees. At this point the area is known as a “disease center.”

Let’s add one more dot, and then connect them all.

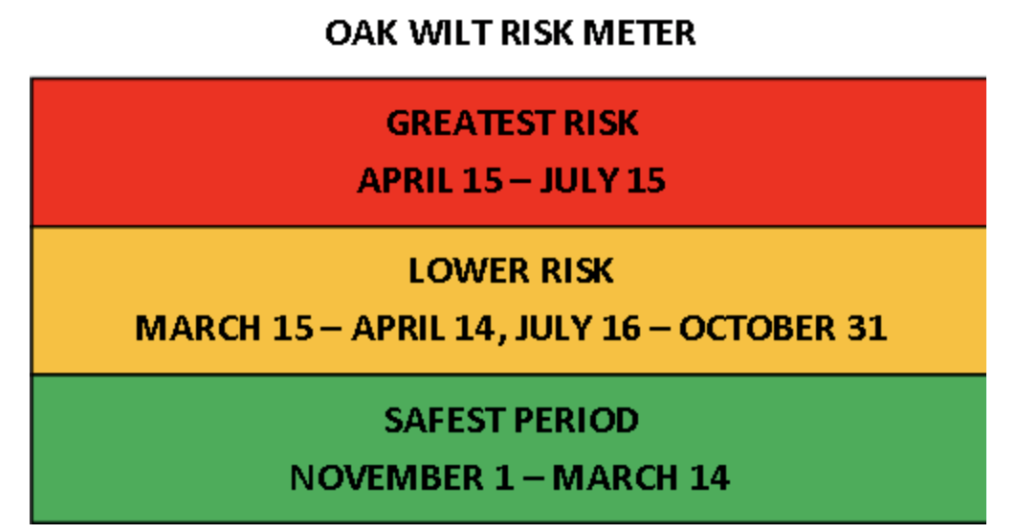

Sap beetles are the most active (in Ohio) in early spring through early summer, from about early April to early July. During this time infection courts are at the highest risk of being visited by beetles which may be carrying fungal spores.There is reduced beetle activity later in the summer, and of course, there is no beetle activity expected when temperatures cool down in fall/winter. For this reason conscientious arborists will converse with their clients about the best time to prune their oak trees.

If pruning is unavoidable (such as for removal of hazardous or storm damaged limbs) the pruning cuts must be painted with latex paint or a suitable wound dressing within five minutes of the cut being made. In the case of storm damaged trees (unexpected infection courts), the trees should be monitored for any symptoms of oak wilt so that steps can be taken to prevent infection of any neighboring trees. One of the methods that can be used to prevent underground infection is by injecting trees with a fungicide that will inhibit disease infection.

The most important part of managing the health of oak trees where the threat of oak wilt exists is choosing the right time to prune. The introduction of a chemical treatment should only be considered when there is a known infected oak in the vicinity. This is an approach that should be discussed with a qualified Certified Arborist who can guide the need for such a decision.

Red to maroon are areas of high risk. Maroon/dark red is highest risk.

Source: Oak Wilt in the Northeastern and Midwestern States: A Story Map by the USDA Forest Service Northeast Region

Oak wilt is not like emerald ash borer, a pest which many of our readers are very familiar with and know that any ash tree that is to be preserved should be on some sort of chemical treatment protocol. If an oak tree is not within root grafting distance of other oak trees, the only management method required is cultural: prune at the time when you are confident there is little or no risk of infection.

If an oak tree is within root grafting distance, pay attention (along with your qualified Certified Arborist) to neighboring trees, talk to the owners/managers of those trees, and make decisions that aid in the preservation of both your tree(s) and the neighboring tree(s).

If you’re concerned about oak wilt the best option is to enlist the aid of your qualified Certified Arborist to help determine if symptoms are indeed oak wilt, or if sampling is necessary for a laboratory test.

We hope you found this article informative and timely. Please share it with anyone you know who has oak trees. One final thought to end on: “Help take care of your trees, and they will help take care of you.”